Roosevelt Elementary School: Teachers Teaching at a Higher Order

Long Beach, California

The capacity for students to be able to apply higher-order thinking skills is referenced everywhere as an ultimate goal of school outcomes in content standards, in textbooks, and on standardized tests. Most teachers are aware of a hierarchy of skills as referenced in Bloom's Tcixonomy of Educational Objectives. For example, they know that synthesis-level questions are more complex than knowledge, or fact-based, questions. However, many teachers are not as cognizant of the kinds of thinking associated with higher-level thinking skills. For many, learning the Thinking Maps was the first time teachers actually had a clear understanding of specific types of thinking skills, how they interrelated and transferred across disciplines, and most important, how the skills worked together to engage and sustain higherorder thinking on a day-to-day basis in classroom settings.

After the training, the positive energy from the teachers from this new understanding and related tools immediately transferred itself to the students in their classrooms. This is because these teachers realized that the focus was on immediate use and translation for students. When I walk into classes and 1 want to know what kinds of thinking the students are learning about and how they are applying these foundational skills to content learning, my teachers can now identify this

because they know Thinking Maps. They can also tell what kind of thinking the students are expected to use. Importantly, Thinking Maps were used to promote critical thinking skills even for students who were still acquiring English.

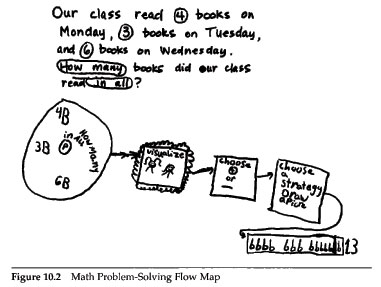

All students in Grades 1-5 were tested on a standardized test in reading and math, and Grades 2-5 were also tested on the California standards test. Much of the math section includes reading. The teachers taught students to analyze the type of math question it was, for example, comparison, whole to part/part to whole, relationships, patterns, e t ~a.n d the map associated with each. Once the students understood the five kinds of "story problems," they were able to tease out the critical attributes of these and apply them to the test. For example, in response to a word problem shown in Figure 10.2, one first-grade student selected the key information from the problem using a Circle Map and then used the Flow Map to show the steps and the strategies involved in solving the problem based on the information in the initial Circle Map. The change in students' ability to do these problems made a significant difference between last year's and this year's school scores.

In our district, students are also required to take a writing test each year that is scored on a holistic scoring rubric. The task is response to literature, which parallels one of the state's required tasks. Although primarily a reading task, students must read a passage and then respond to a prompt. In Grade 1 at my school, students had to read a story and then demonstrate their understanding of the text by using a Thinking Map to demonstrate the sequence of the story and then show how the characters changed over time. Most students used a Flow Map and then a Bubble Map as their response to the task. This type of task gave us insight into the students' comprehension at both a knowledge level (the sequence) and at deeper levels (how the character changed over time), without burdening them with having to write a complex essay.

This was especially helpful for teachers in analyzing the understanding of the English-language learners. The use of the Thinking Maps for this task also enabled the students to read more critically on the standardized test. Kristin Tucker, a first-grade teacher, reflected that "the Thinking Maps took the English language learner to the highest level of thinking. . . in a very simple way. I didn't have to explain in words what I was doing, instead I just exposed the students to the maps and the students just 'got' them very easily. It was so easy that students quickly learned to combine maps by themselves." This facilitated student learning of content, and the explicit transfer of thinking skills by students also provided her with additional time to teach!

Other teachers commented on how they noticed that the type of thinking used in one curriculum could be used in another. Because the teachers were able to make these connections, they were able to help students make the same connections. The results were that students were able to more quickly learn the content once they understood the underlying types of thinking they needed. Instead of teaching specialized skills and strategies particular to one content, teachers began to generalize these deeply within and across disciplines.

More information about Roosevelt Elementary School is part of the book Student Successes With Thinking Maps — read excerpts from this chapter and other chapters about the student successes.